Changing the Course Of Pain Management

Opioid Crisis Has Cos. Looking to Develop Safer Treatments

Monday, January 29, 2018

San Diego — In 2014, Heron Therapeutics took notice of the role of postoperative pain in opioid addiction. So, the company dusted off a shelved drug program.

Heron is among the San Diego pharma and biotechs rushing to market with alternatives to opioids, dependence on which mushroomed into a national health epidemic. Their treatments aim to prevent dependence, overdoses and side effects, but could face challenges like insurance coverage.

The companies are targeting the more than 100 million Americans suffering from chronic pain, but who often have few other options than opioid painkillers.

Along with profits, the companies say they’re motivated to introduce new treatments for the sake of public health. And fast.

“There’s no question the opioid crisis increased the urgency at the company to move this product forward,” said Heron CEO Barry Quart.

Opioid Crisis

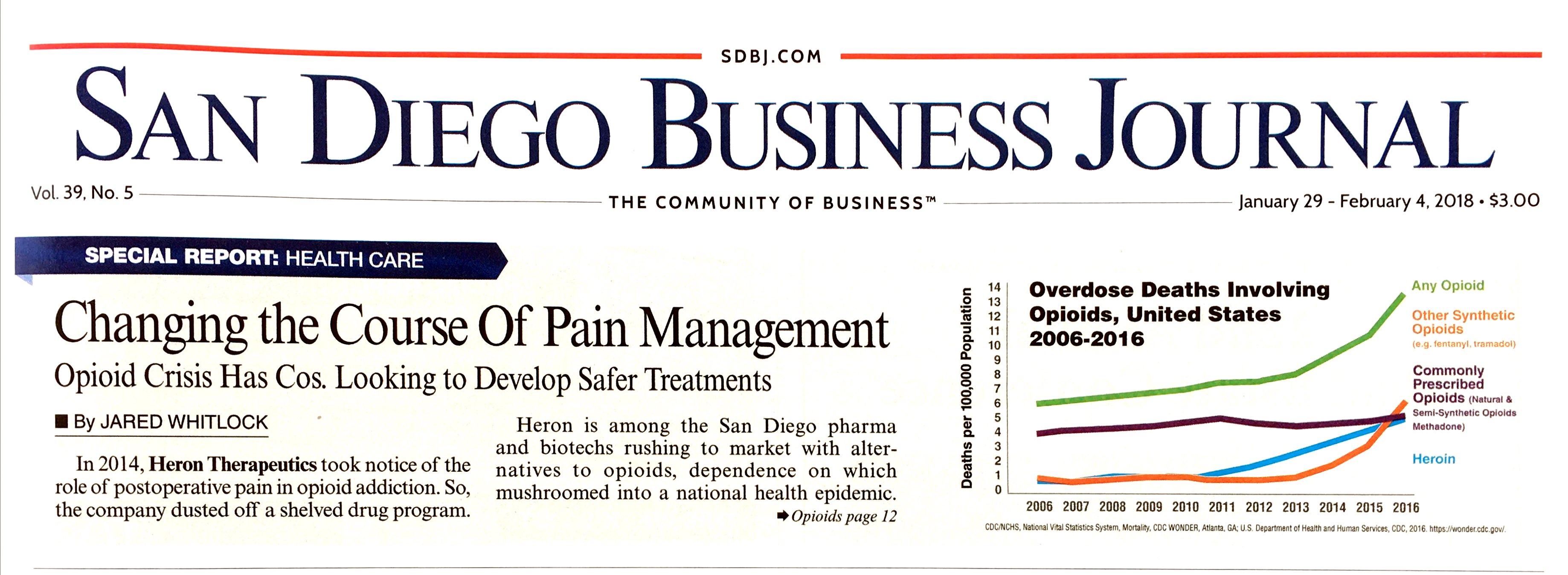

In the U.S. in 2016, there were about 64,000 drug overdose deaths, two-thirds of which were linked to opioids.

Heron is vying for dominant share in a post-surgery market it estimates could reach $5 billion annually. It’s a big opportunity as the company’s current market cap is $1.5 billion.

Its long-acting anesthesia therapy — in final-stage trials — lasts three days instead of a few hours. Compared with a placebo group in phase 2 trials, surgery patients took 74 percent fewer opioids after 24 hours, and there was a 53-percent reduction 96 hours later.

“The first three days is really a critical period of time when the pain is most intense, and patients use the most opioids,” Quart said.

Such heavy doses can translate into addiction. About six percent of minor and major surgery patients who were prescribed opioids continued to use them after 90 days, according to a 2017 study in the medical journal JAMA.

Another study in the same journal last year found more than two-thirds wound up with unused painkillers in the weeks after their surgeries, leaving leftovers often accessible to others in the home.

The treatment, HTX-011, can be traced to a failed opioid-alternative program from the early 2000s. Technology from a later anti-nausea drug, combined with the opioid crisis, convinced the company to give it another go four years ago.

A New Way

Sorrento Therapeutics has a much different plan of attack. Its drug, Resiniferatoxin, directly targets nerves responsible for pain, as opposed to blocking brain signals. “It’s a completely new way of looking at pain management,” said Alexis Nahama, Sorrento’s vice president of corporate development.

Powering Resiniferatoxin: a molecule found in a cactuslike plant native to Morocco.

“The molecule has been around for a while, but no one was working on it as a pharmaceutical compound,” Nahama said.

It’s geared toward cancer patients and aching joints. An injection that lasts six months to a year can soothe, for instance, a throbbing knee that’s otherwise structurally sound.

“We might be able to replace opioid usage in some cases. But we’re also excited because we think this drug has the potential to maintain efficiencies of opioids at the lower levels, and avoid that increasing need to up the dose,” Nahama said.

Opioids Have Uses

He cautioned against demonizing opioids, noting they play a role in some cases.

The company envisions a pipeline of drugs flowing from Resiniferatoxin, still in early-stage human trials. It received orphan drug status from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, lightening the burden of development through more frequent FDA interactions, reduced fees, and extended market exclusivity once the drug is approved.

It’s tough to say whether the drug’s potential in reducing or replacing opioids played a role in securing the orphan status. San Diego companies are hopeful federal recognition of the crisis amounts to a smoother regulatory path for all drugs in various trial phases now.

Reimbursement Factors

Further promise stems from a bipartisan White House commission convened to address the opioid crisis. In November, the panel recommended increased access to alternatives, stating the government and private insurers could do better job on this front.

“They identified, quite specifically, that the way these opioid alternatives are reimbursed in fact incentivizes the use of cheap opioids,” said Quart, Heron’s CEO.

Quart, who has spoken to members of congress on the issue, said there’s bipartisan willpower to improve the reimbursement equation, and insurers are acting on their own as well. Major changes could take a while, though.

Compared to five years ago, investors are paying more attention to non-opioid treatments, due to therapeutic advancements and the topic dominating headlines. So said David Crean, managing director of San Diego’s Objective Capital Partners, who leads the firm’s life science investment banking deals.

Midstage companies and startups largely occupy the space. Crean said large players have steered clear, instead focusing on oncology and rare diseases for surer returns.

“It comes down to risk. Their thinking is, ‘Why take that on when there are so many other things you could be doing?’” said Crean.

But Renew Biopharma CEO Michael Mendez sees a window of opportunity. The startup synthetically grows cannabinoid molecules in microalgae, with the goal of sparking a new class of therapeutics.

To that end, this month Renew announced a pre-clinical drug discovery program in partnership with Indiana University’s Gill Center for Bimolecular Science.

“There haven’t been a lot of great new molecules to manage pain. They’re all opioids,” Mendez said.

Renew’s process doesn’t involve THC or plants, so unlike cannabis-derived drugs, the company said, it wouldn’t encounter development obstacles stemming from the federal government classifying marijuana as a “schedule 1” substance — a dangerous drug with no medicinal value.

Renew has roots in the algae biofuels of Sapphire Energy, a company Mendez co-founded. Renew, which has raised $2 million, holds 110 patents.

“It became clear to me about how bad the epidemic is really getting,” Mendez said, adding “This has become more of a passion for me than biofuels.”

Passion led John Hsu to self-fund his startup Quivive Pharma, where he’s CEO. The company’s tablet combines a breathing stimulant with generic opioids, with the goal of preventing respiratory-related death.

Hsu said the inclusion of an approved opioid paves the way for a quicker regulatory path, and helps ensure competitive pricing, as well as reimbursement by third party payers. Human testing is slated to begin later this year.

The company is also working on a medical device that biometrically dispenses pills at set intervals.

“The problem is not the opioid, it’s the human. They over-consume,” Hsu said.

San Diego seems to have a good number of entrepreneurs who have turned their attention to the opioid crisis in recent years, often for reasons that go beyond money, he said. A former physician, he counts himself among them.

“I’m trying to be a game-changer in medicine,” Hsu said.